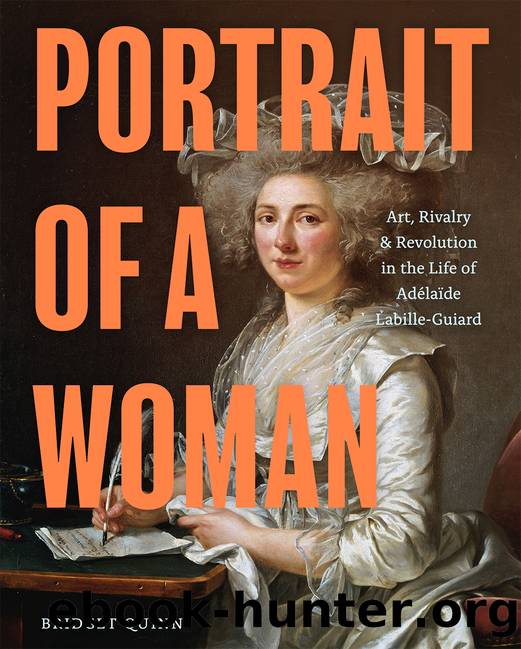

Portrait of a Woman by Bridget Quinn

Author:Bridget Quinn

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Chronicle Books LLC

There had, of course, been plenty of self-promoting self-portraits by artists in the past. Albrecht Dürerâs Christlike visage springs immediately to mind. Artemisia Gentileschiâs Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting (La Pittura). Rembrandt van Rijnâs Self-Portrait with Two Circles. And, of course, Ãlisabeth Vigée-Lebrunâs recent Self-Portrait in a Straw Hat, where she aligned herself with Peter Paul Rubens, and by extension other old masters. Adélaïde had clearly taken note, but she went further. She claimed her own place in a lineage of masters and brought other women with her. Hers is the first known self-portrait of a woman artist at work alongside her students.

Like Ãlisabeth, Adélaïde depicts herself in a straw hat adorned with an emphatic ostrich feather flourish, though on Adélaïde it looks weirder because she is clearly indoors. And while Ãlisabeth wields a charged palette beneath her sunlit visage like some bountiful nature goddessâLa Primavera as La PitturaâAdélaïdeâs vision is somehow stranger for existing in an enclosed everyday space, under brown studio light.

Her scene is a kind of stage set, no less than that of the Horatii. But rather than antique tragedy, Adélaïde enacts a domestic drama where she herself is center stage, spotlighted, and in control, director and actor both. We are her audience. Like Jacques-Louis David, she has a tale to tell, a point to make. Because in addition to needing to drum up sales, she must save her artistic legacy from the danger that threatens it before itâs fully begun.

On May 14, 1783, two weeks before she and Ãlisabeth Vigée-Lebrun were elected to the Académie Royal, the comte dâAngiviller, a kind of minister of culture, had predicted their inclusion. He was willing to concede the battle, but he also sought to win the war. As discussed in Chapter 13, the Académie maintained a tacit quota of four women in its esteemed ranks at any time, but without royal endorsement, this quota never carried the force of official law. When the comte dâAngiviller saw the writing on the wallâthat is, that royal influence would insist on, at the very least, Vigée-Lebrunâs election to the Académieâhe wrote King Louis XVI to strongly suggest a royal decree that would codify the quota of four women in law. âThis number,â he wrote, âis sufficient to honor their talent.â36

In practice this meant that none of Adélaïdeâs noteworthy students (more on them to come) could hope to enter the Académie Royale until one of the current four women died. A grim prospect. And not great for friendship and support among women artists. Not to mention the implied tokenism of the four women already in the Académie Royal, whose work could never be âuseful to the progress of the arts.â Another way of saying, really, that while womenâs art might aspire to be good, it could never be great.

Adélaïde, who had sought assistance from the very same comte dâAngiviller, via his wife, in combatting libelous verses at the 1783 Salon, now mounted her own defense. Like all scrappy ballers, she went on offense.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Technical Art History by Jehane Ragai(469)

Art, Science, and the Natural World in the Ancient Mediterranean, 300 BC to AD 100 by JOSHUA J. THOMAS(418)

Graphic Culture by Lerner Jillian;(404)

The Slavic Myths by Noah Charney(383)

Sketchbook Confidential: Secrets from the private sketches of over 40 master artists by Editors of North Light Books(355)

Pollak's Arm by Hans von Trotha(352)

Drawing for the Soul by Zoë Ingram(350)

Simply Artificial Intelligence by Dorling Kindersley(349)

Treasuring the Gaze by Hanneke Grootenboer(344)

The Art of Portrait Drawing by Cuong i(343)

Drawing Landscapes by Barrington Barber(332)

Mountain Manâs Field Guide to Grammar by Gary Spina(329)

The Art of Painting Sea Life in Watercolor by Maury Aaseng Hailey E. Herrera Louise De Masi and Ronald Pratt(322)

Portrait of a Woman by Bridget Quinn(312)

Anatomy for the Artist by Jennifer Crouch(309)

Botanical Illustration by Valerie Price(296)

Preparing Dinosaurs by Wylie Caitlin Donahue;(296)

A text-book of the history of painting by Van Dyke John Charles 1856-1932(294)

Egyptian art by Jean Capart(288)